Amtrak Year-by-Year: 1981

CommentsDecember 2, 2013

Amtrak marked its 10th Anniversary in 1981.

Thinking back over all that had happened in 1981, Amtrak President and CEO Alan Boyd wrote, “In perspective, [it] was the corporation’s finest hour.” While Amtrak celebrated its 10th birthday, it also experienced ramifications from “an abrupt redirection of federal funding philosophy” under the new administration of President Ronald Reagan.

Boyd highlighted the positive news for the fiscal year: 16 percent revenue growth; four percent growth in passenger miles; 11 percent ridership increase on long-distance trains, primarily credited to the new Superliner equipment; and a 50 percent decline in customer complaints, again attributed to new cars and locomotives. These numbers were all the more impressive considering that the nation had entered a recession in 1980 and the unemployment rate was on the rise.

Since 1971, total revenues had risen 311 percent to $506.3 million, corresponding with a 60 percent increase in passenger miles traveled. In 1981, approximately 21 million customers boarded Amtrak trains at 525 stations spread across 44 states. Ranked against major passenger carriers such as Greyhound, Delta and United Airlines, Amtrak emerged as the country’s sixth largest intercity public transportation company.

Substantial investments in the locomotive and rolling stock fleets led to improvements in on-time-performance and equipment reliability noticed by customers. New single and bi-level cars operated across the system, and older cars were substantially refurbished in-house at the Beech Grove, Ind. maintenance facility. Work also continued on the Northeast Corridor Improvement Project and general station upgrades.

In January, Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as the 40th president of the United States. Believing in a smaller role for government and a need to cut spending, his administration reevaluated federal support for a variety of programs, including intercity passenger rail. Planning for fiscal year 1982, Amtrak asked for federal support of $970 million, while the Reagan administration countered with a proposed $613 million budget.

During appearances before congressional appropriations committees and advocacy groups, Boyd noted that the president’s proposal likely meant that Amtrak would have to stop all service in 36 states outside of the Northeast Corridor (NEC).1 Approximately 14,500 employees would be let go, and the 284 new Superliners—representing a $313 million, six year investment—would go into storage since they were too tall to operate on most long-distance routes originating in the Northeast. Boyd pointed out that about half of the operating budget would be siphoned off to cover required labor protection payments to laid-off union workers.2

Severe budget cuts would have sidelined the new Superliner fleet.

Taking stock of the improvements to the passenger rail system under Amtrak, Boyd had difficulty understanding the administration’s reasoning. In an April interview with The New York Times, he commented, “It would be a tragedy if we get cut off just as we are about to succeed in carrying out the 1970 Congressional mandate to establish a sound national rail system. We have renovated our equipment, improved stations, put new equipment on order, and now they want to lose all of that. It just isn’t right.”3

Boyd and the Amtrak board of directors responded to the president’s budget number by reducing the original Amtrak request to $842 million. In the end, following months of negotiations between the executive branch and Congress, Amtrak received funding of $735 million. Closing the year, Boyd wrote in the annual report, “The Corporation again was placed in the position of defending itself, facing a level of scrutiny and challenge seldom known to most American companies. Yet, the mounting record of achievement stated a persuasive argument for support.”

In response to reduced funding, some routes—generally those with the lowest ridership and cost recovery—were discontinued. They included the Shenandoah (Washington-Cincinnati), Cardinal (Washington-Chicago)4, North Star (Chicago-Duluth) and Pacific International (Seattle-Vancouver, B.C.). Metroliner Service and regular regional services on the NEC were also trimmed. The Inter-American (Chicago-Laredo/Houston) became a tri-weekly train south of St. Louis. Amtrak also initiated workforce reductions, and freshly prepared meals in Dining cars were replaced by microwaved tray meals. On the upside, a positive development was the initiation of the Washington-Chicago Capitol Limited, which was combined with the Broadway Limited (New York-Chicago) west of Pittsburgh and also replaced that train’s Washington section.

In the wake of budget talks, Amtrak stressed the need for a consistent federal funding source for passenger rail. According to the company, it should take the form of a “grant system with the federal government, at a level paralleling the indirect government subsidies all other U.S. public transportation modes enjoy…With budgetary consistency, long-term planning can bring more rapid progress toward declining federal grant allocations and ultimate self-sufficiency.”

Amtrak focused on the long-term by creating a Corporate Development department “to pursue asset utilization and diversification projects to generate additional corporate revenue.” Boyd stressed that “[these] programs are not intended to replace or infringe upon passenger train activities.”

With the purchase of the Northeast Corridor in 1976, Amtrak had taken possession of key real estate holdings in major East Coast cities including Philadelphia and Washington. The corporation began to consider development of vacant parcels and air-rights. A mixed-use project was proposed for 30 acres north of Philadelphia 30th Street Station and Amtrak worked as part of a consortium to develop the Gateway IV office building over tracks leading to Chicago Union Station. By the end of 1981, revenue from leasing of concessions and land amounted to $16.6 million—a 33 percent increase over the previous year.

Amtrak aggressively marketed the skills of Beech Grove employees.

The Northeast Corridor’s prime location—passing through major city centers—also made it attractive to developers of a revolutionary new communications infrastructure: fiber optics. Amtrak entered into negotiations with carriers interested in installing a fiber optic network along the NEC from Boston to Washington. Amtrak would be a commercial user, gain a train service communications system and receive revenue by leasing the space. Plans also called for the company to better market the expertise of craft workers at Beech Grove, where rail cars owned by transit agencies could be overhauled, rehabilitated or assembled.

The search for cost efficiencies also extended to contract negotiations with 15 non-operating labor unions covering employees such as machinists, electricians and coach cleaners. Amtrak sought work rule reforms and a cooperative labor-management approach to increase productivity. The latter resulted in the establishment of the Joint Labor/Management Productivity Council in 1982, in which management and union representatives identified areas of mutual concern, suggested resolutions to existing problems and highlighted potential productivity improvements.

Other long-term investments also came to fruition in 1981, including the completion of the Chicago Maintenance Facility. The five-year, $44 million construction project produced a new locomotive building that protected workers from the elements; coach yard with servicing and storage tracks, platforms and electrical systems; commissary; and other structures. Services previously spread over a half-dozen Chicago facilities were now consolidated, leading to annual workforce and operations savings estimated at $9.2 million.

A popular marketing campaign, “See America at See-Level,” launched with colorful advertisements depicting the gorgeous landscapes visible through every train window. The Marketing department carefully directed its limited budget to the 26 highest potential markets. Outside of the NEC, Amtrak made sure to mention improved ride quality due to $15 billion in recent track and right-of-way capital improvements made by the freight railroads. State-supported programs in New York, Michigan and California also provided significant improvements to the roadbed.

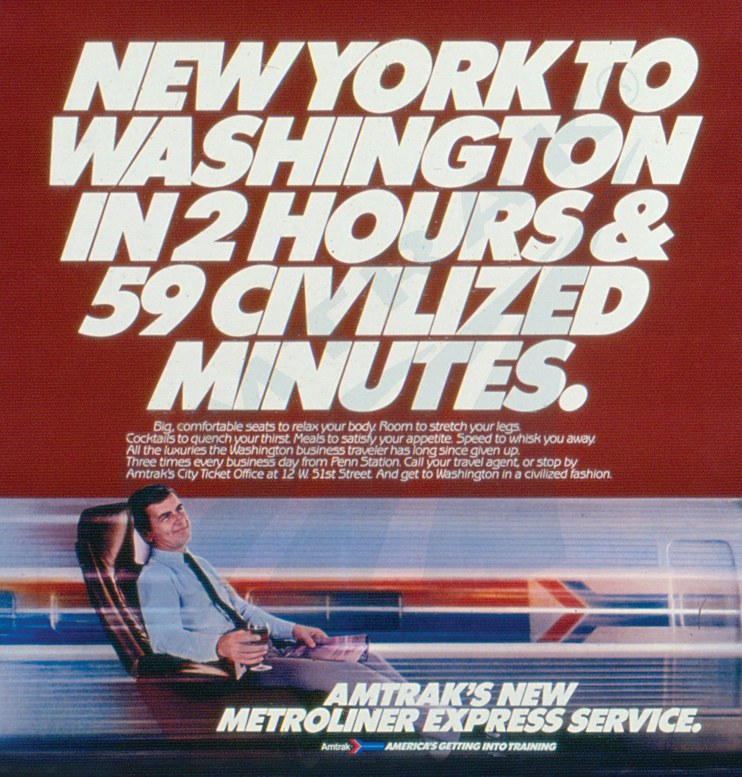

Between Washington and Boston, work progressed on the Northeast Corridor Improvement Project. Although the long-term gains would be great, in the short-term the continuous work and schedule adjustments—including longer train run times—contributed to a dip in NEC ridership. Airline industry deregulation also led to fare wars in the Northeast that hurt rail ridership. In an effort to recapture some of the lost traffic, Amtrak introduced express Metroliner Service trips between New York and Washington whose trip times were less than three hours.

Based on the success of high-speed rail in Europe, Amtrak set its sights on the future by considering the possibilities of a similar system in the United States. Amtrak noted that the company’s first decade had been dedicated to reestablishing and efficiently operating the “conventional passenger train network,” but also foresaw that a high-speed system with dedicated track could “herald America’s entry into the 21st Century for rail passenger transportation.”

Looking to the future, the annual report summed up the keys to “unlocking rail travel’s fascinating new potential” as Amtrak entered its second decade: contemporary contractual arrangements with rail labor unions; development of human resources; capital investment; funding consistency; business development and diversification; and development of high-speed trains. These efforts would be championed by W. Graham Claytor, Jr., a new Amtrak president and CEO who would define the company in the 1980s.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 Carole Shifrin, “Is Amtrak headed for derailment?,” The Milwaukee Journal, May 4, 1981.

2 Ibid.

3 Ernest Holsendolph, “Amtrak Chief Looks to Congress for Aid,” The New York Times, April 26, 1981.

4 The Cardinal was reinstated as a tri-weekly New York-Chicago train in 1982.

In addition to the above links, sources consulted include:

National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Annual Reports for fiscal years 1980-1982.