Amtrak Year-by-Year: 1982

CommentsJuly 18, 2014

W. Graham Claytor, Jr. took the helm of Amtrak

in 1982.

In early May 1982, Amtrak President and Chairman Alan S. Boyd announced his resignation. He had spent a little more than four years at the company’s helm, guiding Amtrak through the Congressionally-mandated 1979 route restructuring and a change in presidential administrations. The prior year, Boyd presided over Amtrak’s 10th anniversary; in that first decade, total revenues had risen 311 percent to $506.3 million, while passenger miles traveled increased 60 percent. Amtrak had grown to become the nation’s sixth largest intercity public transportation company.

Boyd reflected during an interview with The New York Times, “I foresee a bright future for the nation’s revitalized rail passenger network, and thus it is with mixed emotions that I end my direct involvement with Amtrak.”1 According to an interview with Dan Cupper of Passenger Train Journal, Boyd believed he had accomplished three major goals at Amtrak: creating credibility for the company before Congress and the public; reforming labor contracts to be in line with modern business practice; and improving operations, particularly relationships with the host railroads that helped lead to better on-time performance.2

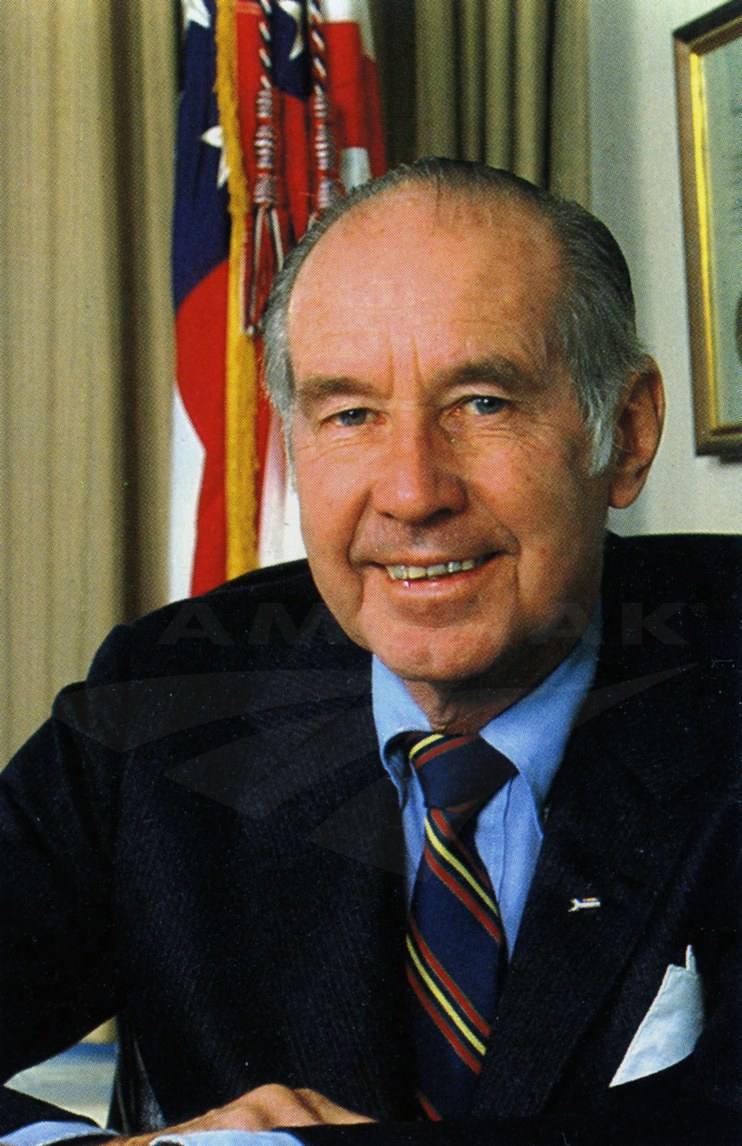

Successor W. Graham Claytor, Jr., named to Amtrak’s top position on June 11, arrived the next month “with the goal of improving every service currently operating and at the same time reducing the costs of operating those services.” He acknowledged his predecessors, noting that their “legacy…is the stability of Amtrak as a system and as an institution.”

Amfleet II coaches and food service cars began arriving in 1982.

A lawyer and World War II naval hero, Claytor gained extensive knowledge of passenger and freight railroading as the vice president, president and chairman of Southern Railway between 1963 and 1977. At the formation of Amtrak in 1971, Southern declined to turn over its passenger services to Amtrak. Although the railroad eliminated its other remaining passenger trains in the mid-1970s, the flagship Southern Crescent (New Orleans-Washington-New York) continued to operate until 1979 when it was then transferred to Amtrak and renamed the Crescent. Following retirement from Southern, Claytor began a second career in government service with the Carter administration. Between 1977 and 1981, Claytor served as Secretary of the Navy, Acting Secretary of Transportation and Deputy Secretary of Defense.3

Although Claytor took the helm of Amtrak during a recession that suppressed ridership, the company still ended fiscal year 1982 with more than 19 million passengers. Amtrak also met an important statutory goal of recovering 50 percent of its total operating costs through revenues—more than three years ahead of schedule.

To reduce costs and improve productivity, Amtrak management negotiated directly with the unions representing non-operating employees. In the past, the company had accepted the same contracts the freight railroads had negotiated with their unions. In May, unions representing ¾ of the total employee force signed agreements, and later that year, Amtrak carried on negotiations directly with the unions representing train and engine crews in the Northeast Corridor. The new contracts provided for an “hourly basis of pay, elimination of supplemental payments, and modernized work procedures.”

To facilitate further discussion between the unions and management, a Joint Labor/Management Productivity Council was created to “examine and recommend improvements in all areas of activity that affect Amtrak’s productivity.” It included a member from each labor organization representing employees, an equal number of management members and a public chairman. The council discussed areas of mutual concern, evaluated working conditions and made recommendations to resolve standing problems.

By 1982, Amtrak completed a multi-year program to convert all of the remaining Heritage Fleet cars from steam to electric head end power. New car development and acquisition efforts undertaken in the 1970s now meant that modern, reliable Amfleet I, Amfleet II and Superliner cars composed approximately two-thirds of the total fleet. The Amfleet II single level coaches and lounges, intended for overnight trains, began arriving that year. For motive power, the 3000 horsepower F40PH, capable of hauling trains at 100 mph, proved the mainstay of the long-distance locomotive fleet; in the Northeast, Amtrak received AEM-7 No. 932, the last in the original 47 unit electric locomotive order.

Freight railroads, over whose rails Amtrak ran its long-distance services, invested $15 billion in right-of-way improvements in the early 1980s; coupled with better operating agreements, Amtrak was able to reduce running times and boost many trains’ on-time performance. One of the year’s most significant achievements was the launch of ARROW, a new nationwide ticketing and reservation computer system. It replaced the Amtrak Automated Reservation and Ticketing System (ARTS), which due to growing call volume had experienced delays and shutdowns. ARROW had ten times the computing capacity and restored an optimal two- or three-second response time.

In the Northeast, the five year long Northeast Corridor Improvement Project (NECIP) was nearing its end. In 1982, Amtrak noted that the Track Laying System, a series of machines that moved along the rails and replaced ties, installed continuous welded rail, cleaned ballast and aligned the track, was close to laying its one-millionth tie. In addition, crews replaced track in the Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel near Baltimore Penn Station, completed maintenance-of-way bases in Perryville, Md., and Providence, R.I., and also finished work on a dozen bridges.

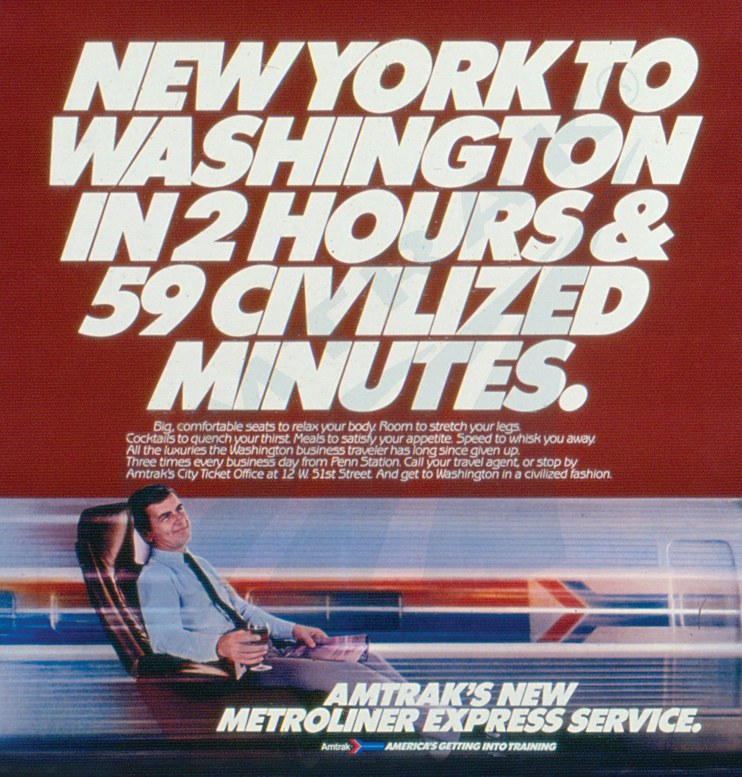

The improved infrastructure allowed Amtrak to bring Metroliner Service schedules between Washington and New York back under three hours; only two years before, major NECIP work meant that some Metroliner frequencies had been stretched to almost four hours. Travelers may have also noticed that the original self-propelled Metroliner equipment was replaced by Amfleet cars pulled by a locomotive.4

Continuing a trend started under Alan Boyd, Amtrak utilized its physical assets and highly trained workforce to win outside contracts representing new revenue sources. Employees at the Beech Grove, Ind., maintenance facility overhauled 15 commuter coaches for the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority, generating $3 million. Amtrak also signed a $9 million contract with Breda Costruzioni Ferroviarie, S. p. A. to assemble 294 rapid transit cars for the Washington, D.C., area subway system.

In hindsight, 1982 marked a time of transition toward newfound institutional stability. In its first decade, the company was led by three men who each put their own stamp on its culture and operations. They had established standard procedures, overhauled the locomotive and rolling stock fleets and guided the company through adjustments to its national route system. Claytor, skilled in both railroading and politics, built on this solid foundation over the next decade and came to define an era.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Daniel F. Cuff, “Business People: Amtrak’s Chairman Plans to Step Down,” The New York Times, May 6, 1982.

2 Dan Cupper, “Drawing a bead on Boyd,” Passenger Train Journal Vol. 14, No. 2 (August 1982)

3 Richard D. Lyons, “W. Graham Claytor, Architect of Amtrak Growth, Dies at 82,” The New York Times, May 15, 1994.

4 Bruce Goldberg, “Metroliner’s Amazing Career: Pivotal moments in the life of America's first high-speed train,” Trains website (June 30, 2006).

In addition to the above links, sources consulted include:

National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Annual Report for fiscal year 1982.

All quotes, unless otherwise noted, are drawn from this report.