Celebrating the Hell Gate Bridge Centennial

CommentsMarch 30, 2017

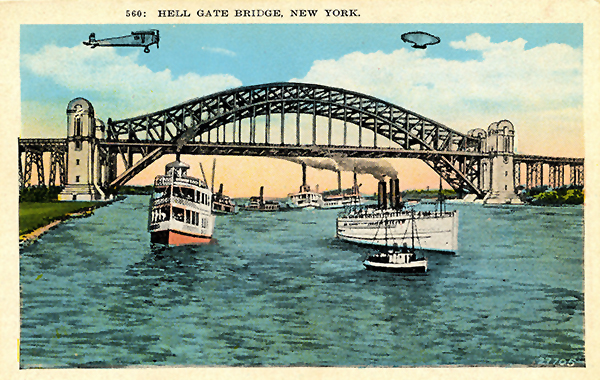

April 1, 2017, marks the centennial of regularly scheduled passenger rail service over the famed Hell Gate Bridge, which is the centerpiece of a complex of bridges and viaducts that links Astoria, Queens, on Long Island, with the mainland in the Bronx via Wards and Randalls islands.1 The bridge takes its name from the narrow stretch of the East River it spans. Here the waters of Long Island Sound and Upper New York Bay meet, creating strong tides; the area once also featured dangerous rapids. Often described in glowing superlatives, the Hell Gate Bridge was the longest steel arch bridge in the world when completed in 1916 and instantly became an icon of American railroading.

The bridge’s opening also largely marked the completion of the Amtrak Northeast Corridor (NEC) as we know it today, providing an all-rail route from Boston to Washington through New York City. Approximately 40 Amtrak Northeast Regional and Acela Express trains cross the bridge each day – as well as freight trains – rewarding customers with breathtaking views of the Empire City’s world-famous skyline.

On March 27, 2017, Amtrak joined with the Greater Astoria Historical Society at its headquarters in Astoria, Queens, to celebrate the anniversary. Speakers discussed the history and construction of the bridge and its impact on the community. Amtrak also emphasized the Gateway Program as a necessary investment in the region’s passenger rail infrastructure for the 21st century. At the close of the ceremony, attendees made a toast to the bridge and enjoyed birthday cake.

New York City’s Railroad Infrastructure at the Dawn of the 20th Century

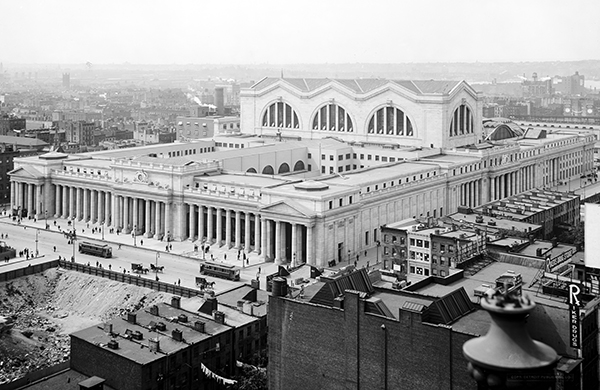

Although a monumental structure in its own right, the Hell Gate Bridge and the railroad it carries were part of a larger vision that reshaped New York’s rail infrastructure at the start of the 20th century, creating better connections between the island of Manhattan and mainland New York and New Jersey. Until the grand, neoclassical Pennsylvania Station opened in 1910 to serve the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), only the New York Central (NYC) and New York, New Haven and Hartford (NH) railroads had direct access to the island, terminating at the shared Grand Central Station.2 Their lines crossed from the Bronx into Manhattan over the Harlem River.

The rival PRR had long dreamed of a Manhattan facility directly serving the country’s largest metropolitan area, dominant port and business center, but the broad Hudson River was a formidable natural obstacle. Most of its passengers boarded river ferries at Jersey City, N.J., to reach Manhattan.

Over the new century’s first decade, the PRR finally achieved its goal of reaching the city. It designed and built a new right-of-way in New Jersey from Newark to Weehawken; tubes below the surface of the Hudson and East rivers connecting with New Jersey and Long Island, respectively – and providing access to the new Pennsylvania Station; tunnels under the streets of Manhattan; and Sunnyside Yard in Queens.

Building the Hell Gate Bridge

Even with these vast improvements, New York City still lacked an easy all-rail connection through the metropolitan area linking the railroads approaching from the southwest and northeast. Railroad passengers needing to pass through the city on their travels were forced to proceed via a ferry, vehicle or foot, adding additional time and inconvenience.

To address this issue, the PRR joined with the NH to break ground on the New York Connecting Railroad (NYCR) in 1910.3 Such a link had been discussed by the railroads for nearly two decades.4 The approximately nine-mile, four-track line, intended to carry both passenger and freight trains, would have a connection to the NH in the Port Morris section of the Bronx, cross the East River, make a swing through parts of still-rural Queens and join the PRR at Sunnyside Yard where passenger trains then headed toward Pennsylvania Station.

>

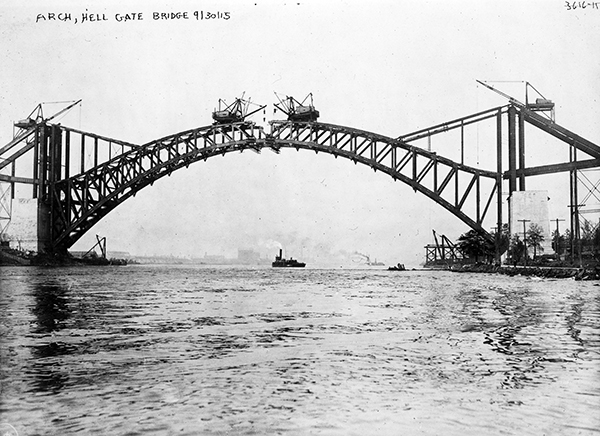

Traveling cranes were used to build out one half of the main arch from each shore. Image: Library of Congress.

Freight trains would continue south past Sunnyside Yard where they switched over to a freight-only line owned by the Long Island Rail Road (then controlled by the PRR) that led to Bay Ridge in Brooklyn. From there, freight cars would be floated across New York Bay to Greenville, N.J., a distance of three miles covered in about an hour.5 This represented a significant time savings over the six hours then required to float cars 14 miles between Harsimus Cove, N.J., and Port Morris.6 At the time the NYCR was built, the NH and PRR were daily interchanging approximately 1,000 freight cars via carfloat.7

The NYCR cost $27 million, with about two-thirds of the funds spent on the Hell Gate Bridge, two smaller spans over the Bronx Kill and the Little Hell Gate (formerly separating Wards and Randalls islands) and the viaducts connecting these elements – altogether known as the East River Bridge Division (ERBD).

This complex was designed by engineer Gustav Lindenthal and architect Henry Hornbostel. The former was a master bridge builder who immigrated to the United States from the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 18748. He had earlier proposed to the PRR construction of a 10-track bridge over the Hudson River.9 Hornbostel was a native New Yorker who trained at the prestigious Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. The two each found early professional success in Pittsburgh, and at the time of the Hell Gate commission had already collaborated on the design and construction of the Queensboro Bridge across the East River (in association with engineer Leffert Buck).

Construction of the ERBD began in March 1912, with 140 workers typically on site.10 They began assembling the signature arch of the Hell Gate Bridge two years later.11 Rising 305 feet above the river’s surface, the steel arch spans more than 1,017 feet between the two towers. The bridge deck, suspended from the arch, measures 93 feet across and carries trains 135 feet above the water.12 Altogether, more than 19,400 tons of high-carbon steel were used in construction, with components manufactured by the American Bridge Company. Workers installed more than 1.2 million rivets to assemble the span.

Due to the turbulent river conditions at the Hell Gate, it would have been difficult to erect temporary false work to support the arch while under construction. Lindenthal chose instead to build out half of the arch from each shore, joining them together on Oct. 1, 1915.13 When the two sections were properly aligned, they came to within 5/16 inch of one another.14

Lindenthal and Hornbostel’s work married the practical with the elegant, important at a time when the City Beautiful movement advocated for public infrastructure that was functional and efficient yet also aesthetically pleasing. On the Hell Gate, this is demonstrated through the addition of the two, 220-foot high granite-clad towers flanking the arch. They actually have little purpose other than to add visual weight and balance to the arch, whose lower chord is anchored to their abutments. Looking closely, the upper chord does not come into contact with the towers.

Structural engineer H.O. Ammann, who worked with Lindenthal, echoed these ideas in a 1918 article about the Hell Gate: “A great bridge in a great city, although primarily utilitarian in its purpose, should nevertheless be a work of art to which Science lends its aid. It is only with a broad sense for beauty and harmony, coupled with wide experience in the scientific and technical field, that a monumental bridge can be created.”15 The Hell Gate’s elegant form and proportions later influenced the design of a similar bridge spanning the harbor in Sydney, Australia.

On March 9, 1917, representatives of the PRR and NH gathered to dedicate the Hell Gate Bridge and associated works. Engineering News noted that in a symbolic gesture, Lindenthal turned the structure over to PRR President Samuel Rea, who in turn gave it to NH Vice President E.C. Buckland, since the NH would operate the NYCR day-to-day as part of its system.16

Coinciding with the dedication, the PRR announced that the first revenue passenger train to use the bridge would be the Federal Express traveling overnight between Boston and Washington.17 Publications such as Dun’s Review, a journal for the promotion of international trade, effused, “For the first time all the important cities of the Atlantic seaboard from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Key West, Florida, are connected by a continuous, direct, all-rail coastal line.”

Investing in Rail Infrastructure for the Next Century

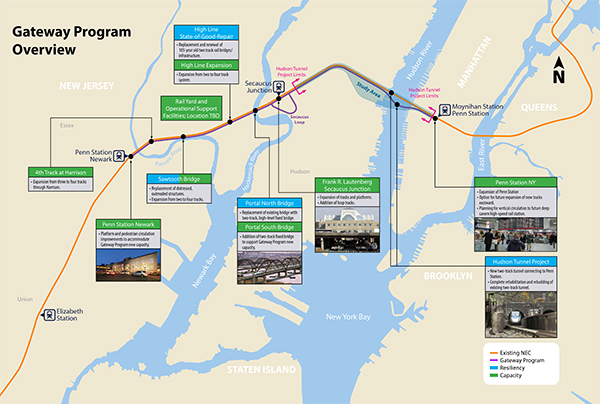

Fast forwarding six decades, Amtrak gained ownership of the Hell Gate Bridge, and the majority of the 457-mile NEC, in 1976. In line with the work of visionary rail leaders a century ago, Amtrak is today implementing its own plan for modernizing rail infrastructure in the New York-New Jersey region. In 2011, Amtrak unveiled the Gateway Program, a comprehensive set of strategic rail infrastructure improvements designed to improve current services and create new capacity that will allow the doubling of passenger trains running under the Hudson River.

The program will increase track, tunnel, bridge and station capacity, eventually creating four mainline tracks between Newark, N.J., and New York Penn Station, including a new, two-track Hudson River tunnel. Gateway also includes updates to, and modernization of, existing infrastructure, such as the electrical system that supplies power to the roughly 450 weekday trains using this segment of the NEC.

By eliminating the bottleneck in New York, the Gateway Program will provide greater levels of service, increased redundancy, added reliability for shared Amtrak, commuter and freight operations, and additional capacity for future service increases. Amtrak has directed more than $300 million, mostly from federal sources, to the Gateway Program since 2012.

As the Gateway Program progresses, the Hell Gate Bridge will continue to play, as it has for 100 years, a vital role in intercity and freight services not only in the New York City metropolitan area, but also greater New England and the Mid-Atlantic. It truly stands as a monument to the ambitions and achievements of American railroading and as a landmark in one of the world’s great cities.

Have you ever wondered what it takes to maintain the Hell Gate Bridge? Learn more in this profile of Amtrak Senior Engineer of Structures Juan Salinas.

1 These were separate islands at the time the Hell Gate Bridge was constructed, but were joined together in the 1960s.

2 The current Grand Central Terminal opened in February 1913.

3 Thom, William G., and Sturm, Robert C. (2006). The New York Connecting Railroad: Long Island’s Other Railroad. Babylon, N.Y.: The Long Island – Sunrise Trail Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Lindenthal was born in Brno, now part of the Czech Republic.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 O.H. Ammann, “The Hell Gate Arch Bridge and Approaches of the New York Connecting Railroad Over the East River in New York City,” Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers (Vol. LXXXII), 1918.

13 “Bridging Hell Gate,” Fall River Line Journal, September 1916.

14 Ibid.

15 Ammann worked with Lindenthal on the Hell Gate early in what became a prolific career. He later designed the George Washington and Verrazano Narrows bridges, among others.

16 “Railway Officials Formally Dedicate Hell Gate Bridge and Viaduct,” Engineering News, March 15, 1917.

17 “Hell Gate Service April 1,” The New York Times, March 14, 1917.